Artigo de David Fideler e Cristian Pătrășconi para o Antigone Journal

“Nos últimos 2.000 anos nosso mundo evoluiu muito em termos de tecnologia. Mas quando você lê Sêneca, percebe que os humanos não mudaram no aspecto psicológico. Somos, psicologicamente, exatamente iguais às pessoas de Roma há 2.000 anos. Sofremos dos mesmos tipos de esperanças, medos, ganância, ambição e vícios que os antigos romanos experimentavam. Também temos o mesmo desejo de nos tornarmos pessoas melhores e mais excelentes. Sêneca explora tudo isso.”

Last year, philosopher David Fideler published Breakfast with Seneca: A Stoic Guide to the Art of Living (W.W. Norton, New York, 2022), a guide to Seneca’s core ideas written for a general audience. In this dialogue with the Romanian journalist and political scientist Cristian Pătrășconiu, Fideler discusses Seneca’s enduring popularity and what we can learn from Seneca and the Stoics today.

Cristian Pătrășconiu: What does a perfect morning look like to you?

David Fideler: Many years ago, I started reading the Roman philosopher Seneca (c. 4 BC–AD 65) first thing in the morning, when I woke up, along with a cup of coffee. Over time, that changed a bit. Eventually, I developed a morning ritual, and on a perfect day, I’d go to the gym, work out, and grab a cup of coffee. I’d then have a delicious breakfast, and while eating breakfast, I’d read a letter or two written by Seneca.

That’s how the title of the book Breakfast with Seneca originated. Reading a bit of Seneca each morning became a great way to start the day, and, over the years, I’ve now read Seneca’s writings many times.

Seneca has been dead for many hundreds of years. But why does a thinker like Seneca continue to live? Why does he still speak to readers today?

I have a PhD in philosophy but only discovered Seneca later in life. What I found so appealing about Seneca is that, aside from being a great writer, he focuses on real-life issues. How do you handle grief when a loved one dies? How do you respond to worries or anxious thoughts, so you can return to living fully and calmly in the present moment? What is real friendship, and why is friendship so important? How can we contribute to society? Everything Seneca writes about is timeless and on our minds today. This makes Seneca seem contemporary. Because he had an incredibly deep level of insight into human psychology, he feels like a wise advisor to many readers.

Over the past 2,000 years, our world has evolved greatly in terms of technology. But when you read Seneca, you realize that human beings have not changed psychologically. We are, psychologically, exactly the same as people in Rome 2,000 years ago. We suffer from the same kinds of hopes, fears, greed, ambition, and addictions the ancient Romans experienced. We also have the same desire to become better, more excellent people. Seneca explores all of this.

Seneca has been called “the most compelling and elegant of the Stoic writers”. Where does such appreciation come from? Wasn’t Marcus Aurelius also a very elegant and persuasive writer?

Seneca was an expert in rhetoric, which makes him a compelling writer. In addition, he has a unique literary style, which was imitated by others, stretching from the Italian Renaissance to Ralph Waldo Emerson. This engaging style makes Seneca a pleasure to read, and his work is full of little epigrams – sayings like, “When someone doesn’t know what port he’s sailing for, no wind is favorable” (Epistulae 71.3).

Of course, I agree with you that Marcus Aurelius was an elegant writer. But Marcus Aurelius was only writing for himself in his private notebooks. Those were never meant to be published, and it’s a miracle that they survived and have come down to us.

By contrast, everything that Seneca wrote was addressed to one of his friends or family members. That’s because he thought philosophy should help real people in the real world. Seneca also believed that his works would be read by “future generations”, to use his phrase, which turned out to be true. So while Marcus Aurelius was writing notes and observations for himself, Seneca was writing for us.

Could we say that Seneca is “the Stoic par excellence”?

That would be a difficult judgment to make since it would be based on personal taste. But Seneca was the Stoic par excellence historically speaking. For example, the humanists who created the early Italian Renaissance had access to all of Seneca’s writings in Latin, and they were deeply influenced them. In terms of ethics, Stoicism was about becoming more virtuous as a person, and it was a remarkably pro-social philosophy. Renaissance humanism was a movement to create a more humane and virtuous society with better leaders. In this way, the writings of Seneca helped to ignite early Renaissance humanism, which was a revival of ancient virtue ethics. The humanists also drew upon the ideas of Cicero, a Stoic-inspired philosopher, whose ideas of civic virtue expanded upon Stoic ideas.

Later in the Renaissance, when the Italian humanists learned to read Greek, the writings of the two major Stoics who followed Seneca – Epictetus and Marcus Aurelius – were published. But they seemed to have had very little impact at that time.

Marcus Aurelius is hugely popular now, but that is a very recent development. He only started to become popular in English in the 19th century, and he’s at peak popularity today. But people have been reading and learning from Seneca for 2,000 years.

If you carefully study Seneca, Epictetus, and Marcus Aurelius, you’ll discover that they were largely expressing the same ideas, but each in their unique way, because they were addressing different audiences. Of course, since they were all Stoics, that’s not surprising. The ideas of Epictetus were recorded by his student Arrian, but even his most famous idea, which people call “the dichotomy of control” today, is found in Seneca’s idea of virtue versus Fortune. Virtue, or our inner character, is “up to us”, while Fortune is “not up to us”.

So which Stoic writer does a reader like the most? In the end, it’s a matter of personal taste. But historically speaking, you can find almost every important Stoic idea in Seneca’s Latin writings and the writings of Cicero, even if you don’t read Marcus Aurelius or Epictetus. That’s why people in the early Renaissance understood Stoicism very well, even when Marcus Aurelius and Epictetus were not yet available.

In any case, Seneca is the Stoic thinker from whom we have the most works. Many texts, especially of Greek Stoicism, have been lost, right? About how many of these – let’s say in percentage terms – do we still have today?

Stoicism originated in Athens around 300 BC and was founded by Zeno of Citium. Zeno, a merchant interested in philosophy, came to Athens from modern-day Cyprus. Eventually he lectured on philosophy at the Stoa Poikilē (ἡ ποικίλη στοά) in Athens – “the Painted Stoa”, which is where the school obtained its name.

Zeno and his followers, the early Greek Stoics, wrote a huge number of works in Ancient Greek, but those works never came down to us. We have long lists of their titles, so we know at least what those were about. We also have some very short quotations from the Greek Stoics, but the original writings were lost. What we have from the Greek Stoics is less than one per cent of what they wrote. That’s why the writings of Seneca and the other Roman Stoics are so important, even if they are from a later time, since they had access to Greek sources that no longer exist. Seneca left us hundreds of pages about Stoicism. So yes, he’s the largest single source.

Is Seneca a thinker easier to understand in youth or maturity or, better, in old age?

That’s very hard to say since everyone’s tastes are different. In the United States, people of all ages are interested in Stoicism, and there’s huge interest among young people. Everyone interested in Stoicism has a favorite Stoic, and for some people that is Seneca. Others prefer Marcus Aurelius or Epictetus.

Seneca, at one point, became one of the richest men in the world. But isn’t immense wealth inconsistent with Stoic philosophy?

Seneca’s wealth was partly due to his talent, but also due to chance, luck, or “Fortune”, as he would say. But being wealthy doesn’t go against the principles of Stoicism, especially if someone makes good use of wealth. Seneca addressed that question at the end of his essay De vita beata (On the Happy Life).

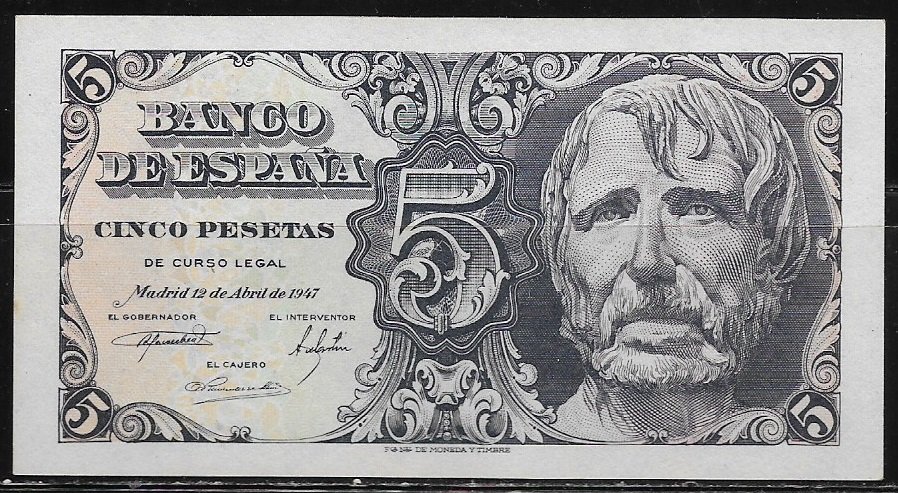

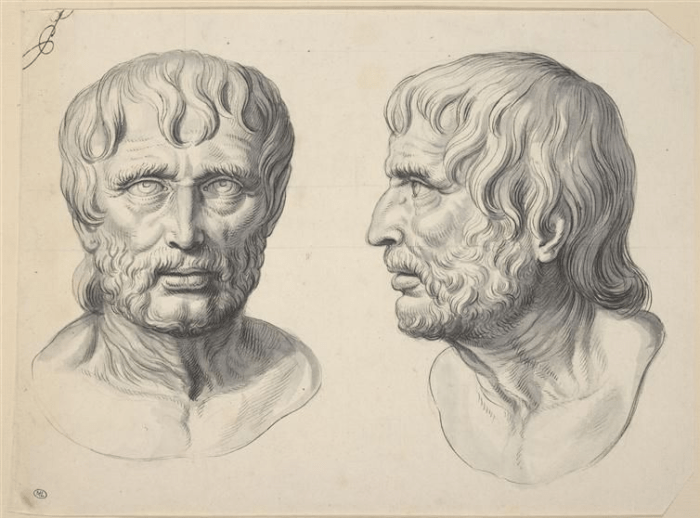

Seneca was born in Spain and, when he was very young, his father took him to study in Rome. He started studying Stoicism as a teenager in Rome. Later in life, Seneca rose to the peak of Roman society and became a Roman senator. He then became elected consul, the highest political office anyone could hold. So his career mirrored, in some ways, that of Cicero.

In terms of his wealth, Seneca experienced good fortune. But he had a lot of bad luck too. First, he was a senator under Caligula (r. 37–41), who reportedly wanted to kill him. Then he was a senator under Claudius (r. 41–54), who exiled him, under false charges, to the island of Corsica. Seneca was finally called back to Rome eight years later to become the tutor to Nero (r. 54–68), when Nero was only eleven years old.

Of course, being associated with Nero turned out to be bad luck, too, but no one could have known that at the time, since Nero was only eleven. He became emperor just before he turned seventeen, and it’s thought Seneca and Burrus, the head of the Praetorian Guard, ran the Roman empire for the first five years, when Nero was so young.

Like some wealthy people today, Seneca attracted a few enemies simply because he was rich. While wealth has obvious benefits, Seneca wrote about its dangers. For example, he explored how great wealth can make some people psychologically unbalanced. When it came to wealth and its misuse, Seneca “had seen it all”, as we say, including greed and extravagance at the highest levels of Roman society. He concluded, “The poor person is not someone who has too little, but someone who always craves more” (Epistulae 2.6).

Seneca wrote extensively about the problems associated with wealth, and he believed that living a life of voluntary simplicity was psychologically beneficial. In Breakfast with Seneca, there is an entire chapter about Seneca’s views on money, voluntary simplicity, and using wealth wisely. It’s entitled “The Battle Against Fortune: How to Survive Poverty and Extreme Wealth.”

Can we say that the Covid-19 pandemic worked as an accelerator? In other words, can we say that that it was good for Stoicism and, in particular, for Seneca?

That’s true because interest in Stoicism surged during the pandemic. When people were in lockdown, the writings of Seneca and Marcus Aurelius skyrocketed in sales. It’s easy to understand why this happened because a central idea of Stoicism is that things that happen in the world are rarely “up to us”.

The Stoic view is that we can’t control things that happen to us but we can control how we respond to them. So Stoicism is a perfect philosophy for a pandemic – or for a time when there is a great deal of uncertainty about the future. If we don’t let our minds race ahead and become anxious, we can respond to things rationally, just as we do in the present moment, without worry. The Stoics remind us that when the future finally does arrive, we will be able to respond to all future situations calmly and rationally, just as we do today. That is because “the future” will have become the present moment, which is free from worry.

A question that follows from the previous one: is Stoicism more useful in times of austerity, in times of crisis, than it is in happy or bright times?

On the surface, it might seem that Stoicism is more helpful in times of crisis, but I don’t believe that’s true. Seneca was especially mindful of the cyclical nature of human experience. He would frequently point out that when things are going very well and people are flying high psychologically, they must be cautious and prepare for a decline. Because once you reach the absolute peak, you can only go down. As Seneca said, “The high places are the ones hit by lightning” (Epistulae 19.9).

Similarly, when things go poorly, or someone hits bottom, they will often improve. He wrote, “After a shipwreck, sailors try the sea again… If we were forced to give up everything that causes trouble, life itself would stop moving forward” (Epistulae 81.2).

What, in your view, is the central message of the teachings we received from Seneca?

Seneca believed that we should always work on trying to improve our character. Each day, he thought, we should try to make a little bit of progress to become better or more virtuous. For human beings, to be virtuous means to be rational, and a rational person will embody the four cardinal virtues: practical wisdom, courage, moderation, and justice. But, in the Stoic view, these virtues can only become realized by practising them. So it involves working on the process every day, which includes self-reflection.

Another attractive Stoic idea is the belief that we can live a life that is truly worth living under any conditions. Again, Seneca writes about this at great length. He writes about how we can make progress each day and live a joyful life.

From another point of view, is Seneca a great guide for life or a great guide for death?

Both – because going back to Socrates, it was said that “philosophy is a preparation for death” (Plato, Phaedo 81a). According to Seneca, how we face death, when it finally arrives, is the ultimate test of our character. For many people, death is the supreme fear, and Seneca wrote about how to overcome that anxiety.

For the Stoics, there is nothing dreadful or fearful about death; it’s just a natural part of life, which everyone will encounter. All the Roman Stoics said that someone on their deathbed, who developed a good character during life, should not be sad or filled with regret at death. Instead, they should be grateful for the life and experiences the universe has given them.

What was philosophy for Seneca – an academic, vanity game, or did it have a major existential stake? And could we still understand today that, in antiquity, philosophy was closely related to friendship?

Seneca is quite clear about that: he believed that friendship and philosophy go together. He wrote, “The first promise of real philosophy is a feeling of fellowship, sympathy, and community with others” (Epistulae 5.4). In ancient times, the philosophy was a joint undertaking. Seneca believed we should pursue it with others in a spirit of friendship and common inquiry.

Seneca was also critical about what philosophy had become. Even in his own time, it had become a mere “academic pursuit” for some people – or, as you put it very nicely, “a vanity game”. Seneca criticized those who reduced philosophy to empty, unconvincing arguments or to mere “word games”. Like earlier philosophers, he thought philosophy was a way of life – and an “art” or skill designed to improve human life and reduce suffering. As the Greeks had called it earlier, philosophy is “the art of living”.

What are the kinds of philosophical exercises the Stoics used and wrote about, and what, from your point of view, are the most essential exercises?

The Stoics had an entire group of philosophical or psychological exercises, many of which relate to modern cognitive psychology. In other words, these “philosophical exercises” are very close to practices recommended by cognitive therapists today. This connection exists for a reason: the Stoics invented what is now called “the cognitive theory of emotion”. In fact, the modern founders of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) read the Stoics, and they drew upon Stoic ideas when creating CBT.

The central idea behind cognitive therapy is that “It’s not things that upset us, but our beliefs about things,” which was taken directly from the Encheiridion of Epictetus (Encheiridion 5). What is fascinating is that the Stoics described psychological techniques that only were given names by psychologists very recently.

I can tell you about my three favorite Stoic exercises. These are simple exercises that anyone can use, and they are very worthwhile.

The first exercise is Socratic questioning, which involves taking a serious look at the beliefs or opinions you have that are causing you to react emotionally in a certain way. Socrates said, “The unexamined life is not worth living” (Plato, Apology 38). If we extend that thought to today, we must try and understand our underlying assumptions and the outcomes those beliefs lead to.

The second exercise I call take a step back, which psychologists call “cognitive distancing”. For example, if you feel anger coming on, Seneca says “the greatest cure for anger is delay” – so take a step back (De ira 2.29.1). For Seneca, becoming angry is a three-step process that involves making certain judgments. The only problem is that it can happen so quickly. So, according to Seneca, we need to step back and slow down the process, to delay the onset of anger. That delay gives us time to think things over. Hopefully it provides a space to deconstruct the anger before it fully takes hold.

My third and favorite Stoic technique, though, is just to suspend judgment before all the facts are in, and that’s another practice recommended by Seneca. Doing this keeps people from jumping to premature and incorrect conclusions, which I often see happening. Of course, everyone has done this. For example, you’ll send someone an important email and never hear back. Then it’s easy to imagine, “Oh, that person hates me”, or “They have ghosted me”, without a single piece of evidence. It’s just an assumption, and there’s no hard evidence to back up any of those beliefs. It might just be that the person never received your email.

Even when there is ‘evidence’, it might not be sufficient. We’ve now seen many cases of people on the internet making premature judgments about a video clip or a news item based on incomplete information or false assumptions, which turned out to be incorrect. So I always avoid making those kinds of snap judgments until all the facts are in, which can sometimes take a very long time.

As we grow up during childhood and beyond, we absorb many bad mental habits and beliefs from society, and the Stoics knew that too. So they would like us to understand those bad habits; and once we can see them, the Stoics invite us to replace those bad habits with better ones.

David Fideler is a philosopher who writes about how Classical and Renaissance ideas can contribute to today’s world. His book Breakfast with Seneca: A Stoic Guide to the Art of Living has now appeared in sixteen languages. He’s also the editor of the Stoic Insights website and the Living Ideas Journal, and the author of the article “How Philosophy Changed the World”, which documents how Seneca, Cicero, and Stoic ideas inspired the early Renaissance humanists.

Cristian Pătrășconiu is a political scientist, essayist, and journalist in Romania. He is the author of several books and a frequent contributor to the weekly magazine România Literară, published in Bucharest.